Scotland in Space

Paul F Cockburn explores Scotland’s often overlooked Science Fiction legacy

by Paul F Cockburn

Scotland in Space – Creative Visions and Critical Reflections on Scotland’s Space Futures, edited by Deborah Scott & Simon Malpas is published by Shoreline of Infinity/The New Curiosity Shop (2019).

“Most of Scotland is ‘rural’, yes, but a sizeable swathe of it is very definitely urban; and over the past two and a half centuries the contributions of Scots to science, engineering and industrialisation have been enormous.” So wrote David Pringle, in his introduction to the 2005 anthology Nova Scotia: New Scottish Speculative Fiction, published by Mercat Press.

However, one thing puzzled the former editor of Interzone, the UK’s longest-running new Science Fiction and Fantasy magazine: “It has always seemed to me that there should have been more Scottish SF writers, especially in the light of the recurrent ‘modernising’ tendencies in Scottish history […] when Scotland has shaken off the dead weight of its past and bounded ahead in certain vital respects.”

Until the explosive literary arrival of Iain M. Banks, and then Ken MacLeod, however, Pringle suggested that notable Scottish writers of Science Fiction simply didn’t exist; this, despite the country’s immense contribution to Britain’s industrial revolution. ‘Clyde-built’, for example, had long become a globally recognised indicator of quality technology and engineering. And yet: “so much of the culture of Scotland, especially the literary culture, does seem backward-looking and anti-urban, mired in Celtic mists,” he suggested.

So where did they go, all those ‘missing’ Scottish SF writers? Pringle had his own theory—Scotland’s SF writers had always existed, but their antecedents had been part of the country’s long history of emigration. As a result, the country’s ‘first wave’ of SF writers appeared not in Scotland, but America. As proof, he noted that the four leading proponents of ‘Space Opera’ were “probably all of Scottish ancestry”. John W. Campbell and Edmond Hamilton, of course, had clearly Scottish surnames, while E E ‘Doc’ Smith and Jack Williamson came, respectively, from decidedly Scottish-sounding Presbyterian and Southern US State backgrounds.

There’s an attractive simplicity to Pringle’s theory, except that – of course – it fails to recognise just how many Scottish writers, from the late 19th century onwards, did at least occasionally write what we would now term Science Fiction. Curiously, Pringle in his introduction, dismissed claims for Robert Louis Stevenson’s Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde, which he felt was “more horror fantasy” than science fiction. Yet surely the same could equally be said of that other alleged founding text of Science Fiction, Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein?

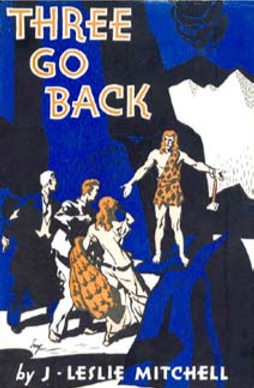

Such literary definitions are problematic, of course, given that the likes of Shelley, Stevenson and his Scottish peers (such as J M Barrie and Arthur Conan Doyle) were largely writing before current genre categories had become entrenched in both our bookshops and our minds. Yet it’s fair to ask why James Leslie Mitchell, arguably Scotland’s nearest rival to H G Wells, isn’t remembered now for his two fascinating (if somewhat naive) Science Fiction works – Three Go Back, and Gay Hunter – but rather for his A Scots Quair trilogy of novels, written under the pseudonym Lewis Grassic Gibbon?

Snobbery? Or is it simply because, particularly during the 20th century, Scottish literature’s genuine struggle to be taken seriously in contrast to British – English – culture, had encouraged an innate association between literary ‘relevance’ and social realism? After all, while English SF writers, from Christopher Priest to Jeff Noon and Robert Rankin, show little difficulty setting their work in England, relatively few Scottish SF or fantasy writers have actively chosen to set their stories in a recognisable Scotland. Interestingly, when they do – for example, Andrew Crumey’s Mobius Dick and Sputnik Caledonia – they receive significantly more mainstream literary attention than their supposed Science Fiction peers.

Nevertheless, the “visionary thread woven through Scottish story-telling” noted by Neil Williamson and Andrew J Wilson – the editors of that 2005 Nova Scotia anthology – has frequently expressed itself “in a sense of the otherworldly”.

Admittedly, authors such as James Hogg and George MacDonald drew their inspiration chiefly from Celtic myth and Border ballads—the latter’s Phantastes: A Faerie Romance for Men and Women (published in 1858) in turn influencing English fantasy writers such as J.R.R Tolkein and C.S Lewis. In more recent times, this strand of Scottish literature could be said to have peaked with Alasdair Gray’s Lanark; yet, like Jekyll and Hyde, Lanark’s status as a modern literary classic also means that we often fail to recognise that its sections set in the dystopian Unthank are undeniably Science Fiction.

While no overtly Scotland-based writers in the early 20th century could be said to have wholly embraced the rise of ‘scientifiction’, there were definite exceptions—David Lindsay’s 1920 debut novel, A Voyage to Arcturus, with its vision of a man seeking physical and psychological transformation on an alien world, remains influential, not least (again) on Tolkein and Lewis.

Nevertheless, some critics were still surprised when Naomi Mitchison, who had used SF tropes for great allegorical affect in many of her short stories, finally produced an overtly Science Fiction novel (in 1962) with Memories of a Spacewoman. Yet, while many 20th century Scottish writers at least dabbled in Science Fiction – several of John Buchan’s supernatural tales are arguably SF (not least Space—in which a mathematician trains himself to perceive higher dimensions) – they remain either isolated within the context of the writers’ wider careers or, as with Jekyll and Hyde, so successful that their influence upon, or debt to, SF is obscured.

Science Fiction, despite what Pringle might have thought, has long been Scottish literature's Hyde: shadowy, glimpsed, often reviled, yet devilishly hard to separate from its accepted face. And, just as in Stevenson’s novel, Scottish literature’s Hyde side would appear to be on the ascendant. Which is surely apt; might not the SF novel be a better vehicle for exploring a world where our lives are increasingly enveloped by science and technology?

It’s impossible, of course, to speak of Scottish Science Fiction without mentioning the late, much-missed Iain Banks who, for many years, alternated between writing equally successful ‘mainstream’ and Science Fiction novels, the latter supposedly (but not always) distinguished by the additional middle initial ‘M’ (for Menzies).

Having an author of Banks’ commercial success and standing undoubtedly encouraged a generation of authors — many linked through Science Fiction fandom and long-running writers’ groups — to focus on the genre exclusively rather than flirt with it like their predecessors. The result is that many of the most notable English-language Science Fiction writers of recent years – such as Gary Gibson, Leeds-born Charles Stross, Finnish-born Hannu Rajaniemi – are based in – or have strong connections with – Scotland.

Last year, Ken MacLeod – arguably Scotland’s leading SF writer – contributed an introduction to the recently-published anthology Scotland in Space: Creative Visions and Critical Reflections on Scotland’s Space Futures (Shoreline of Infinity). The book brings together new Science Fiction short stories and science fact responses, all created in deliberately-nurtured dialogues between authors, scientists and humanists.

At a basic level, this collaborative process simply highlighted how, as the astronomer Alastair Bruce pointed out, there’s “no reason your imagination can’t get some of the physics right”. More importantly, though, it contributed to imaginative explorations of how Space – and, in particular, the planet Mars – were actually of genuinely ‘Scottish’ interest. A new take on ‘Clyde-built’, you might say.

As MacLeod points out in his introduction: “We really are now building spaceships on the Clyde. Scotland’s space industry is booming, and sites from Machrihanish to Sutherland are boosted as future spaceport sites.” If nothing else, the stories published in Scotland in Space at least conceive of Scotland as a place where the cosmic can genuinely happen.