Ceum air Cheum / Step by Step

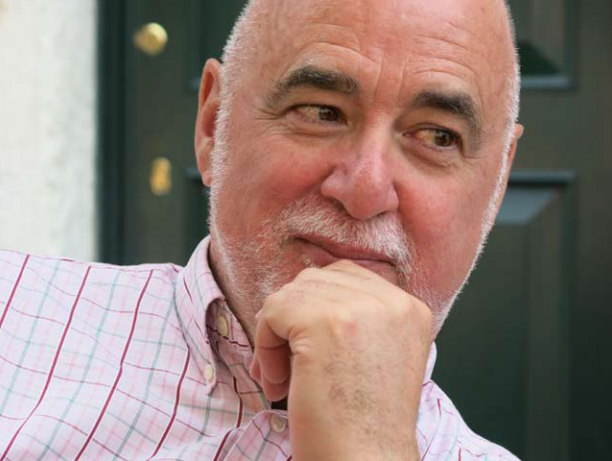

An interview with Christopher Whyte

by Jennifer Morag Henderson

Christopher Whyte’s poetry collection Ceum air Cheum / Step by Step was shortlisted for both the Saltire Society Poetry Book of the Year in 2019 and the Best Poetry Book (Derick Thomson Prize) 2020 by the Gaelic Books Council. It is an audacious book in many ways, from the subject matter to the language it is written in, covering a wide-ranging variety of subjects from the politics of language and translation to suicide and child abuse. Sharp and unafraid, it contains poems about the author’s difficult life experiences, and his writing in Scotland and in Gaelic – including a sometimes-difficult relationship with Sorley Maclean – all set within a European context. It is a collection that has taken almost 20 years to come together, a cumulative group of experiences that have been thought about for a long time.

JMH: One of the things that struck me about the poems was their format: first of all, the fact that this is a book of ‘longer poems’. I don’t think this is a very common format for contemporary Gaelic poetry, am I right?

CW: The most common format for poetry in Gaelic has for some time been shortish poems in relatively free verse, often topical or diaristic in nature. So you are right, the poems in Ceum air Cheum tend to swim against the current in this respect.

JMH: The poems are very rhythmical: smooth and wonderful to read out loud. The rhythm must come early on in your conception of the poem – can you speak about how you start to write – with a word, an idea, or with a line and a rhythm?

CW: Rhythm is indeed fundamental because all the poems are written in metre, often very strict. This counters the apparently “non-poetic”, “prosaic” subject matter, asserting that what you are reading is very definitely poetry, if of an unusual kind. My characteristic metre is an adaptation to Gaelic of English “iambic pentameter”.

I find it very hard to say where a poem “starts”. A novel can start with a powerful image, or a situation, or the relationship between two people. At times a poem can be launched into the air on the basis of translating someone else’s poem. Borrowing and then adapting that particular tone of voice.

Probably for me a poem starts with a tone, an angulation or intonation of the voice, a way or a possibility of saying something. Deciding on the metre takes time. My image for that is, cutting a piece of cloth at the point where it falls from the edge of the table. The choice you make about where to end the first line will be hugely influential for the development of the rest of the poem.

One element that fascinates me is running the sentence structure “against” the metre in a constantly varying counterpoint. What I mean is, not having the beginning and ending of a sentence coincide with the beginning and ending of lines but rather occur halfway, or one third, or two thirds of the way through. My image of that is a cat gradually settling down into a comfortable position. The end of the cat’s tail corresponds to the last words of the sentence and the full stop to its tapering conclusion.

The poem addressed to Sorley Maclean is a virtuoso piece in changing metres throughout. The opening section imitates, in an ironical way, a traditional song metre, which of course comes over as odd without the melody, while the last is cast in “amphibrachs” - groups of three syllables, of which the central one carries the stress, with four in each line. That worked surprisingly well and also felt appropriate in a poem from one poet to another.

“A Face That Won’t Be Etched Along The Crest Of The Cuillin /

Gnùis Nach Dealbhaichear Air Bearradh A’Chuilithinn

When next I go north

I won’t see your face

etched along the crest of those mountains.

I didn’t see them

when they buried you,

my presence that day was not needed. …

Nuair a thèid mi gu tuath

Chan fhaic mi ur gnùis

Air a dealbhadh fad bearradh nam beann ud.

Cha robh iad nam shealladh

Nuair a thìodhlaic iad sibh,

Cha b’fheumail mo làthair-s’ an uair sin. …”

JMH: In "A Face That Won't Be Etched Along the Crest of the Cuillin" [the poem about Sorley Maclean], I like how you make the distinction between the poetry and the man. In today’s ‘cancel culture’ people want to know so much about the internal life and thoughts of the writers they admire, and sometimes seem not to be able to like any of their work if they disagree with any viewpoint.

CW: The phrase “cancel culture” is completely new to me. I myself see no real need for public exposure of the author in readings and in interviews. Take the case of Elena Ferrante, whose identity is still far from being clear. That has done her books no harm. Generally I am ill at ease when reading my own work in front of an audience. It is something I have to steel myself to do and can feel unseemly and inappropriate. A breach of decorum. After all, reading a book or a poem is quintessentially a private experience that cannot always or easily be shared with other people.

Returning to the points I raised about writing in metre. I am pretty sure that rhythm and metre evoke in the reader or listener a psychological portrait of the person who is talking and will help them evaluate how trustworthy this person is, as well as the balance between emotion and thinking behind what they say. Two poems in Ceum air cheum dealing with particularly awkward and disturbing subjects - ‘Sealladh san Duibhre’ and ‘Aig Uaigh Nach Eil Ann’ - observe the relevant metrical rules very strictly. What matters is, the metrical regularity giving the reader the assurance that, however extreme the experiences and emotions being discussed, someone retains overall balance and control. Things are not going to get out of hand and overall the situation is safe. However daunting and unsettling the exploration being undertaken, a guiding hand is there for them to hold onto. That hand is represented by strict metre.

JMH: Some of your poems talk about some highly personal experiences, and I sometimes think that forming difficult experiences into poems, into art, makes them understandable, easier to cope with in some ways. They become formalised and controllable – I had felt what you said about the metrical rules in those poems. But publishing these personal experiences can be a different experience to writing about them, as people can critique not only writing style, but content. I wondered if you would want to say anything about your experience writing and publishing ‘Aig Uaigh Nach Eil Ann / At A Grave That Is Not There’?

CW: When you ask about reactions to the publication of ‘Aig Uaigh’, it brings home to me the unbelievable pressure on people who have been abused to keep silent, even after they have spoken out. Of three siblings in my family, only my sister chose to refer to it, in hostile, suspicious and unsympathetic terms. It was a milestone for me when I realised that if the other family members refused to discuss the matter of my abuse, that by no means indicated they did not believe me. Quite the reverse! One friend said immediately ‘Oh, I wish you hadn’t told me that!’ while at least two others chose to talk about how tough it was for them handling the news, rather than about how it had been for me as a child coping with the abuse.

“At A Grave That Is Not There /

Aig Uaigh Nach Eil Ann

…If someone were to ask what sort of face

evil has, I wouldn’t say, the face

of a head of state, of some general

who has a whole army at his command,

nobody famous, not the murderer

featured in the newspapers, so no-one

can possibly doubt the crimes that he committed,

but rather a face that’s banal, everyday,

such as the man that sells the morning papers,

or else the one remarking to his neighbour,

while they are standing in a bus stop queue,

how unpredictable the weather is.

Or your own face, maybe. My mother’s face. …

…Ma dh’iarrar orm gu dè a’ ghnùis bhios aig

an olc, cha fhreagrainn gur h-i ghnùis aig ceannaird

stàit, air neo cinn-feadhn’ àraidh is arm

fo smachd, no gnùis sam bith tha ainmeil,

eadhon an tè aig murtair nochdas anns

na pàipearan-naidheachd, is nach fhaod teagamh

a bhith aig duin’air aingidheachd a ghnìomh’,

ach gnùis tha dìreach coitcheann, cumanta,

gnùis an fhir a bhios a’ reic nam pàipear,

mar eisimpleir, no chanas ri a nàbaidh

mar a tha an t-sìde caochlaideach,

is iad a’feitheamh air a’bhus sa chiuda.

No do ghnùis fhèin, is dòcha. Gnùis mo mhàthar. …”

Christopher Whyte reads a further extract from “At A Grave That Is Not There” online at the Northwords Now website.

JMH: Some of the translations in the book are by Niall O'Gallagher, and I know that you don't always translate your Gaelic work and have strong opinions about whether or not Gaelic poems should be published with an English translation. Can you speak a bit more about this?

CW: Ideally there ought to be a situation where even long and demanding poems can be published in Gaelic alone and will encounter a competent and appreciative audience in that language. Unfortunately such is far from being the case. Accompanying the “real” poem with translations is a matter of necessity. At the same time, I am certain that translations enrich and expand the original they are working from. Poems benefit from being translated! They are never quite the same afterwards. Translation opens up and discovers possibilities in them that might otherwise be overlooked. That insight strikes me as profoundly alien to the literary world in Britain today, ultimately so hostile and indifferent to translation, isolated in the beleaguered fortress of English, which seeks only minimal interchange with other languages of Europe or of the world. In this respect, writing in Gaelic, and being forced to seek out translators, represents an asset.

When I began publishing poetry in the late 1980s, it was practically obligatory to supply an English translation which could appear alongside. For me, translating a poem into English damaged my relationship to it, as if someone had inserted a foggy plate glass window between me and it. That disturbed me and upset me. It also worried me that magazine editors and prize committees regularly made - and still make! - judgements on the basis of the facing Engish version, without having any qualms about not bothering to learn Gaelic so they could evaluate the poem itself. I have to confess that, when I translate someone else’s poetry into Gaelic, or English, or Italian, the translation tends to oust the original and take its place. Naturally I don’t like this happening when the original is my own and I am also the translator!

For more than a decade Niall’s work as translator of my poems was fundamental. If he had not stepped in to provide English versions, I do not think most of them would have appeared in print. I used my own translations in Ceum air Cheum when these had already been published, and also with two poems – “To a Young Scottish Poet” because this polemic against so-called “relay translation” is pretty barbed, and “At a Grave That Is Not There” because of the extremely personal nature of the message being conveyed to my mother.

“To A Young Scottish Poet, Who Wrote That It’s An Exceptional Occurrence When Someone Knows The Language They’re Translating From /

Gu Bàrd Òg Albannach, A Sgrìobh Gur E Suidheachadh Àraid A Th’ Ann Nuair A Bhios Neach Eòlach Air A’ Chànain Às A Bheil E ’G Eadar-Theangachadh”

… What I felt for you was pity,

diligently employed making soup

thinner still than what you had to start with,

busily pursuing a shadow’s shadow.

Whoever cast it moved, brilliant, unshackled,

Far away, heading for somewhere else

while you, or some of you at any rate,

paced up and down inside the cage of English …

… Bha mi duilich air ur sgàth,

is sibh gu dìorrasach a’dèanamh brochain

nas tain’ dhe bhrochan bha tana mar thà,

toirt ruaig air sgàile sgàil’, ’s an neach a thilg e

siubhal ann an làinnireachd a dheòntais,

an àite eile, dol an seòladh eile,

fhad ’s a tha sibh, no feadhainn dhibh co-dhiù,

ceumnachadh sìos is suas an cèids’ na Beurla …”

JMH: I was particularly struck by the poem "To a Young Scottish Poet". I found it extraordinary at first that a translator wouldn't know the language they are translating from, but when I thought about it I realised I had read poems that were done this way. There's a quote I've read from Douglas Dunn that "only an indifferent poem gets lost / In its translation". When and how did you start working with Niall O' Gallagher?

CW: Niall O’Gallagher was an outstandingly brilliant student in his year at Glasgow and I had the privilege and pleasure of being one of his teachers in the Department of Scottish Literature. He approached me with the proposal of putting some of my poems into English and I was delighted to accept. I did, however, warn him that close association with an out gay man on the Scottish literary scene risked producing a degree of “guilt by association”. Even if homophobia can no longer be expressed as uninhibitedly as in the recent past, it is still a significant factor in how people respond to and evaluate poetry such as my own. Niall took my concerns on board, rolled up his sleeves, and went ahead, with excellent results.

JMH: I am a little surprised to hear those concerns – about him being associated with a gay man in the Scottish literary scene – do you still think this is the case nowadays? I can see that it was an issue in the past, but I felt that attitudes had changed?

CW: I would say that being a gay writer continues to be problematic in Scotland today, even for those coming from a younger generation than my own. Homophobia is still there. It has merely gone underground, evading direct expression.

JMH: One of the reasons I wanted to do this interview was that I thought some of the notes you've been putting on Facebook recently have been so interesting: they come up on my feed in amongst other totally unrelated posts and sometimes I’m not sure what I'm reading at first - whether it is fiction, or an essay, your own thoughts from now, or something from earlier, or the thoughts of a character. I enjoy the engagement that's needed with each post. One of those notes was on 'Discovering you are not English': these questions about Scottish identity are not new, but what I found fascinating about Ceum air Cheum was the way it did seem to take Gaelic somewhere new: I feel that Gaelic is the medium, but not the whole message - the point of the poems is not solely that they are in Gaelic. You are using Gaelic as a working European language and in a way that gets you to the heart of community: people, not just nature, or a fixed point in the landscape and history.

CW: That is spot on, and very perceptive. The language in which it is written cannot always be the most significant aspect of a poem. My gambit - and my gamble! - has always been to treat Gaelic “as if” it were just another modern European language, even though that is not really the case. That sets me apart from a lot of Gaelic writers today, almost in a compartment of my own. Reading other European poets in the original language, and featuring quotations from them above my Gaelic texts, is one element in this approach. Not something I do casually!

One danger with writing in an underprivileged or threatened language is what I call “reification”. You are only permitted to write about certain subjects - the language itself, the community which uses it, their preoccupations and concerns - whereas under normal circumstances, a language can and should be used to deal with any topic whatsoever.

People using Gaelic should not be subject to limitations which are not imposed on writers in English or in German. It is rather like behaving “as if” Scotland were already what so many of us hope it can soon be - an “ordinary” smaller European state like Denmark or Luxemburg or Slovenia. And with creative literature, acting “as if” has a way of almost magically making things come true. Literature has the power to bring into being realities which did not exist before.

Concerning the old debate about who Gaelic belongs to, and who has the right to use it, I have settled on a very straightforward rule of thumb. A language belongs to anyone who uses it. What could be simpler or more clear?

I am so glad to hear that you were following the Facebook posts, and that you enjoyed reading them. The whole idea came from my dear friend here in Prague - where I am writing from now - Petra Poncarová, who won a prize for her translation of Tormod Caimbeul’s Deireadh an Fhoghair, done directly from Gaelic, and who is a regular contributor to Steall. I took a break from weekly postings over the summer but am planning to resume them in September.

This interview was conducted via email and Skype, and has been edited for length and clarity, with the permission of the interviewee.

Christopher Whyte and Jennifer Morag Henderson read a further extract from “At A Grave That Is Not There” online at this website.

↑