Poetry Reviewed by Ian Stephen - Autumn 2020

A Review by Ian Stephen

User Stories

C D Boyland

Stewed Rhubarb, 2020

Disappearance/north sea poems/

Lesley Harrison

Shearsman Books, 2020

Letter to Rosie

Ross Wilson

Tapsalteerie, 2020

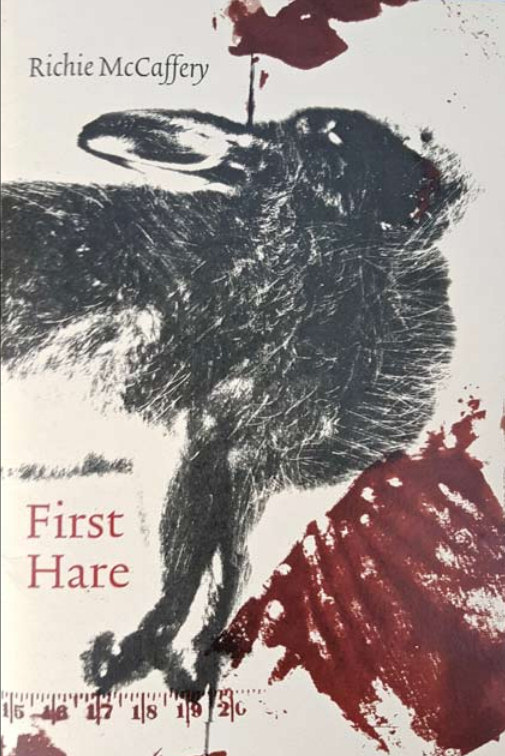

First Hare

Richie McCaffery

Mariscat Press, 2020

In Good Time

James McGonigal

Red Squirrel Press, 2020

Poetry review by Ian Stephen

Here are four new books of poetry, all single author collections and all published in this difficult year. The publishers deserve a cheer as much as the authors. All productions show a level of care and commitment to the cause of bringing their poets’ work out to seek its audience. The appearance and feel of these books is going to help.

Within the limits of a wire-stitched, 24-page booklet with no spine, both typography and design emphasise the contemporary feel of the poems in ‘User Stories’. These are mainly in lower case and often use unconventional signals for line-breaks and rhythm shifts. But other poems like ‘The Puppet’ use a more orthodox orthography and even a narrative with a sting in the tail. There’s a literary nod to Pinocchio but older myths and the oral literature of Homer are also alluded to. ‘The Sirens’ is full of twists and ironies. Its arguments are convincing:

‘…heroes need swords, blood, war &

death to make a world. we need only song.’

Maybe all readers of poetry have a shelf to place pamphlets or volumes which have the satisfying feel that make you return to them. Mine has Lesley Harrison’s collaboration with Orkney artist Laura Drever, in its hand-sewn small form (Brae Editions 2011). Shearsman, publishers of this first full length collection, are also the publishers of poetry by the social anthropologist Tom Lowenstein. Lesley Harrison’s close scrutiny of the culture of mariners who dare pass over the steep shallows of North Sea territories reminds me of Lowenstein’s detailing of the mythology of the Arctic. The range of ambition in ‘Disappearance’ is immense. Characters range from surfers to trawlermen. Chosen forms can nod to Becket and Cage with distinct words highlit by faded ones and all-but-lost ones. But they can also evoke the 20th century ballads of W H Auden:

‘We’ll weave the grasses into hours,

And when the hours are gone

I’ll gather up my coat of earth

And take the road alone.’

‘Lizzie Fairy’ is another ballad, this time in a guid Scots tongue. From oral history to logs of past voyages, the source materials are wide in range. Sometimes the concept seems more crucial than crafted language, especially in the evocation of the Donald Crowhurst tragic voyage (the subject of many studies - most famously those of Tacita Dean). The lost voyaging artist, Bas Jan Ader, is referenced in a photo-based image. Navigating all these shifts of style, visual and poetic, takes a significant commitment from the reader. For now, this one is intrigued, but it’s too early to say if this is a book that insists that you return to dive in deeper.

In stark contrast, ‘Letters to Rosie’ is a harmonic series of poems to welcome a daughter. This is fittingly served by a simple and no-fuss black type on white pages but stapled to a subtle 3 colour cover. There is variety in the chosen stanza form, (6 line to five, to four and to no breaks.) Half rhymes or more irregular chiming of sounds are used to strengthen what comes over as an intimate music. It all seems felt and artless. The poems are moving but they v def ain’t artless. The verse is thus all the more effective when a wee jump is made:

‘I didn’t mention nights

drawing in. I kept it light

as the leaf lifted from

the gutter in your palm,

and you muttered au’um.’

Like most Mariscat publications, Richie McCaffery’s 32-page collection is a handsome production which leaves you with a sense of experiencing something much greater than you might have thought possible in such a light package. As with Red Squirrel books, there’s a quiet but completely appropriate aesthetic. In this case, the cover image illustrates the poem that provides the title but also catches the tone of the whole collection. The series of personal meditations and family studies build steadily until, too soon, you have reached the conclusion.

This could have taken the form of a 1000-page memoire but the amazing thing is that all these lives and a deeply personal revelation of a life lit by love emerge so naturally. There is no suggestion of jam-packing too much in. The art is in a straight-talking narration, close to matter-of-fact but judiciously highlit when it really counts. From the context, I could suss that a ‘spelk’ is a skelf in England’s Northeast. The word ‘peg’ is as plain as it gets, but in the context of ‘Falling’ is perfect in a sustained series of narrations on ‘free-fall’ in the family. This brew is hopped but at least as dry as the districts ales tend to be:

‘but he’d already laced his gene-pool

with a desire for descent.’

That on-run of the sentence over the line break is typical of the most restrained crafting throughout this collection. From the flex in the nib of a family fountain-pen to the thought of a beard likened to biro scratchings, this poet makes confident marks and turns phrases of accuracy and wisdom. I’m going to have to order another couple of copies for friends, because I know I’ll want to return to these engaging sketches of lives, sad though they can be. Take this final couplet of McCaffery’s portrait of a brickie with ‘back and bladder gone’:

‘As he crumbles bit by bit, the young

put up walls all around him.’

James McGonigal is known and respected as an academic with, for example, his biography of Edwin Morgan (Sandstone Press) selected as the Scottish Research Book of the Year. I’ve enjoyed individual poems, encountered in journals. Now, in this exemplary production, his second from Red Squirrel Press, the publisher has judged cover, colours, paper and design to complement the expert typography of Gerry Cambridge. The production does justice to the considered but adventurous work of a master poet.

It’s difficult to describe how this skilfully judged grouping of six distinct series of poems is so vital. The form of the book might sound a bit too well-planned if you simply say how the progression of movements is defined. But let’s give that a try:

‘Get Set’ catches slo-mo snapshots of a childhood world speeding by to first loves and first motors.

‘Far-fetched’ takes you further out into a world, caught in shift of intense natural light, up in the air and down to the ocean as well as glancing on hedgerows.

‘The Desert Mothers’ are notebooks in verse, imagined from actual historical travellers’ narrative.

‘Approaching Autumn’ is a series of linked verses, composed in the character of three poets of different times but with a shared sense of place.

‘Star-Fetched’ has the tone of Neil Young’s ‘After the Goldrush’ and nods perhaps to the mental high-jinkery of Edwin Morgan in seriously playful mode.

‘In Good Time’ puts a new layer to ‘marking time’, with a range of voice from that of a retreating Roman centurion to a Lutheran ‘soul register;’ in Norway.

Throughout this range of subjects, voice, time and place, there is a consistent sensibility. The poet’s skill results in the most rewarding aesthetic. Yet, in individual poems as well as in the overall composition, this is a poet who doesn’t mind making a bold stroke. He’s disrespectful in the best way, able to trust the right to re-imagine things. In this guy’s world, the most mundane of everyday activities ring with significance;

‘And on another day he compared history

to bubbles in a pot of porridge, their pechts

and vanishings. Our mouths across each bowl

must cool that simmering, and eat.’

This is from ‘A Month of Teachings’. Any risk of solemnity is disrupted by the sheer power of the imagery and judicious use of a word: ‘birl’ or ‘feart’. In ‘Boxing Day’ the myth of the robin’s red breast becomes, accurately, a ‘tomato soup stain’. That’s not the only risk of cliché, gladly taken and so a phrase revitalised. Breaking spray is a tricky thing to catch on camera or in language but what about this:

‘Meantime that fist of sea still pummelled rock.

Stars of sweat flew off a boxer’s head.

Take that. And that.’

Line-breaks, rhymes or half-rhymes are used only when they add something – similar to the approach in Ross Wilson’s work. When James McGonigal adopts the haikai form (used for the imagined correspondence between poet and monk Caedmon, Edmund Spenser and Basil Bunting) I felt no hint of strain or squeezing. Clear observation seems more important than any tuning of syllables:

‘CaedmonButterflies tackle bent flowers

like bairns learning to walk.’

‘Wonder’ might be the key word to appreciate how these words arrest you:

‘I wonder which school those trees all attended

to learn how to doze on one leg, poised.’

Really, I want to quote from each poem. The best way to use the generous space this fine journal provides for discussion is to urge the reader to buy this book too. I’d normally post books I’ve read to folk I’m currently corresponding with but I want this one ready to hand so I’m just placing a wee order with Red Squirrel Press. I’d suggest you do that too if you have a taste for superb craftsmanship, worn lightly, and lit by both empathy and knowledge. But all these poets and publishers need support. In the present climate, they seem to me an antidote to the disregard for truth and the inability to empathise displayed again and again by the ‘leaders’ of both the UK and the USA.

↑