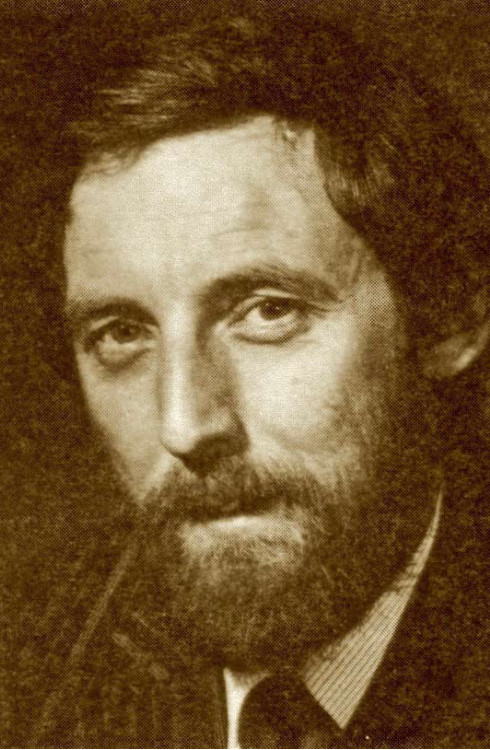

David Ogston

An Appreciation

by Alistair Lawrie

Syne tak a makar.

Woman or man, the same spierin raxes them:

Foo the wecht o wirds can cairry faat they see. (Fechts)

This article began in a Red Cross shop one Saturday afternoon when I picked up a wee thin book with a faded greeny cover that looked as if it had been left out in sunlight too long. I almost didn’t bother but, looking inside, I found it was written in what looked like Doric Scots. My immediate response was that it would be sentimental, badly written, kailyardy stuff, particularly as it seemed to be about growing up on a farm near Auchnagatt. I expected lengthy disquisitions about how the author’s mither made broth (if I was lucky) or more likely a gristling list of names for the forty seven different kinds of graip used on the farm alongside a detailed contemplation of the various uses to which they might be put. Still it was only 50p so I bought it to see what it was like. At that price it hardly mattered. I only started to flick idly through it later that night after coming home from the pub. Three hours later I’d finished it and was enthusiastically firing up my laptop to see what I could find out about the author. Why?

Partly because growing up in the area he grew up in and at roughly the same time many of his experiences paralleled mine living as I did less than a dozen miles away. But mainly because I’d realised with growing and genuine excitement that I’d found a writer who appeared to have created that Holy Grail for those of us who write in Scots and particularly Doric, a readable Doric prose. And I’d never heard of him before.

“I look at the haill picter, for that’s faat it is. This is the story o a place, a country, nae in narrative bit in expressions. … this picter is nae life frozen, bit life, for a brief meenit bringin intae focus aa the loyalties, the loves, the meanins an the values that faistened them tae een anither an the braid land that ringed them.” (Dry Stone Days)

This picter is by a writer that should be better kent in his native Buchan. His name was David Ogston. “Was” sadly because, as I discovered to my enormous disappointment that night, he’d died some years before. My intention had been to get in touch with him to discuss what he’d achieved. There were however two further volumes to his autobiography to be checked out.

David Ogston was born in Ellon in 1943 and brought up on a farm just outside Auchnagatt. He went to Inverurie Academy then took two degrees at Aberdeen University, the first in Arts, the second in Divinity. After graduation he was assistant at St Giles in Edinburgh before becoming minister at Balerno followed by the kirk of St John’s in Perth where he was till he retired. Sadly, he died quite a young man in 2008. He made a name for himself as a minister and was a popular religious broadcaster, often heard on BBC Radio Scotland, and he loved to use Doric whenever possible. He even wrote a special marriage service in Scots, concluding it with: “May they aye win farrer ben till een anither’s herts.” His obituary in the Times called him one of the most creative ministers in the Kirk o Scotland. He wrote a couple o books of prayers and sermons called “Scots Worship”, both still in print.

Bur he also wrote a bourrach of poems, some of which can be found in the Elphinstone Institute’s site as part of their “Kist” and, more importantly, he wrote a three volume autobiography about what it was like to grow up in Buchan in the forties, fifties an sixties. They’re called “White Stone Country”, “Dry Stone Days” and “Grey Stone Zion” and frankly I think they’re wonderful. I’m sorry to say that all three books are out of print. An shouldna be.

The books are a fair delight to read. They’re funny and philosophical; they deal with traditions but also with the modern world as it was then. They give a detailed picture of life on a farm for a wee loon but they also speak about his later love of jazz and blues music, the poets and writers that influenced him, lassies he took out, his own intellectual growth. And all in Doric. The best place to start is with a short passage in which he describes reading Lewis Grassic Gibbon for the first time:

“Grassic Gibbon wis a map markin nae places but experiences. The story he tellt came fae somewye close at haun, the characters fae deep inside masel. They said things, … that I’d heard masel in the spik o the big fowk; they said oot loud things I’d thocht an sensed an reached for, an been gey near tae lauchin at for they winted the validity o print – tull I saa them in front o me, the unspoken said, the unsayable made definite …” (White Stone Country)

The full quote is longer and richer but there’s enough here to make clear not only the powerful effect reading Gibbon had on him as a boy but also to show the quality of prose it inspired in Ogston himself.

What struck me most forcibly on that first reading were two things. First that, after a page or so, it was extremely easy to read despite the unfamiliarity that even a Doric speaker feels when confronted by our native speech in print as prose. I found this deeply reassuring.

By and large the Doric Ogston presents the reader with is fairly easily read for anyone who speaks the language. He spells words as he’d say them but keeps enough of English spelling not to make it unintelligible. If the only appropriate word available is English he doesn’t hesitate to use it. And why not? This is how we mostly speak. Even my granda would occasionally reach for an English word if he felt it appropriate. Just think. There is a recognisable difference between saying “Wid ye dee at?” and the emphasis implicit in “Wid you dee at?” He avoids the trap of raiding the SND for words not current since the Middle Ages and by doing so creates I believe a usable prose. His orthography largely works but there are some failures. By the time I’d read “havers” three times I was seriously puzzled about what he meant until the context of the fourth occurrence made clear that he meant going halves with someone, what I’d have spelled as “halvers”.

The second and more important feature of his writing, however, is the way in which he is able to utilise the language to discuss such a wide variety of subjects. He can be couthy, dealing with his experience of close-knit family life while growing up on the farm, but always with a precision and vigour to his expression that embodies his boyish enthusiasm. For example, describing how he and his father “cowpit weet stooks roon tae the win ae nicht”, in his imagination he is a:

“fechtin chiel oot on a nicht manoeuvre, the shaves wir faes, sentries sleepin at their posts. I crept up on em an breenged at their heids an warsled em tae the grun. Afore they kent fit wis happenin I’d cut their thrapples an they wis aa goners.” (Dry Stone Days p42)

The excitement and joy of that memory is caught precisely. Or he’ll shift to equally lively reminiscence of the things that fascinated him as a boy, the snow cutting the farm off when it “pounced at nicht”, his excitement at a variety show in a local Town Hall, his boyish pleasure in heroes such as Dan Dare or Davy Crockett or Johnny Ramensky “brakkin oot an gien the bobbies a reid face.”

His observations are often perceptively sharp as when he comments on how “the spoken wird, mesmeric in its ain richt, took on a wecht o its ain in the moo o the public man that spak for a livin”, the auctioneer. The texts used as epigraphs throughout are like a statement of intent and demonstrate how the book concerns the growth of a man of intellect, taken as they are inter alia from Saul Bellow, Dennis Potter, Norman MacCaig, Dylan Thomas, leavened by Alison Uttley and a quote from “Timothy Puddle”. This is most evident in the last volume dealing with his time at Aberdeen University where the focus ranges from his studies, the books that had most influenced him to date, the girls he chatted up to his taste for blues and jazz on Saturday night at the University Union:

“.the cornet-player is a brosy chiel, nae exactly Bix Beiderbecke, bit he gies it aa he’s got an the place is shakkin wie the licks an riffs he conjures up.“ (Grey Stone Zion)

Hardly has he finished describing how “the neist drum solo is finally gyaan tae rattle the foons o the Union tae crockanition” before he’s telling us how afterwards they’d “cowp throwe the door” of the chip shop next door to demand “Twa fish-suppers, extra vinegar, wie ingins, an a mealie puddin!”

In a list of his heroes in the same volume he mentions Jackie Hather, Sonny Terry, Paul Tillich, Acker Bilk, Chris Barber, Eliot, Corso, Ferlinghetti, Kerouac, Bonhoeffer and Orwell; he adds “Jackie Hather played for Aiberdeen in the 1950s.” For me one of the greatest delights of his writing is the easy and natural way in which he can shift from the purely local to the lyrical to matters of intellectual weight without ever losing that ease of expression in his own tongue. He can shift from:“he’s a thorough-bred optimist bit he still gyangs tae Pittodrie”to commenting on John Updike’s “Rabbit Run”:“Some beuks ye faa ower, they trip ye up, ambush ye faan ye’re nae expectin it”.This is no accidental use of Doric. In a revealing section he deconstructs:“tak an tirr this littlin. She’s tummelt in o the horse troch an she’s drookit like a droont moose”arguing that its alliterative and assonantal effects are “absolutely typical o the nettral wye we lat the music in, even fan we dinna think aboot it … This alliteration a feature o the wye we spik an the wye we write.” Here is a man consciously shaping a usable Doric prose based on intelligent analysis of its “music”. His effort, his achievement, must not be left to wither on the vine.

Ogston created a believable, readable Doric prose that can deal with the intellectual as well as the homely, that can deal with life now and not be rooted in the past and yet hardly anyone knows his work. Of course it’s out of print. The recent growth of Doric teaching in schools and in Aberdeen University should have these volumes enshrined in their syllabuses.

…

I’m hopin that fit ye’ve read has gart ye think aboot readin some mair o’t. As I said he’s oot o print but aa three are available tae order fae the Library Service. Tae finish I’ll ging back tae far I startit wi fit he scrievit aboot the effect readin Lewis Grassic Gibbon had on him “the unspoken said, the unsayable made definite.” He spiks aboot his experience wantin the validity o print. Fit he felt was that Gibbon gied him that validity gied him permission tae be able to write aboot his ain experience in his ain tongue. Ogston does the same, certainly for me, and gin ye’ve ony love for i wye we spik I’d urge you tae ging awa an read thae books. Or are we tae be deaved forivver by foo mony wyes we can spik aboot graips?

(Readings from David Ogston’s work by Alistair Lawrie for Aberdeenshire’s Library Service and the Across the Grain Festival can be found at https://tinyurl.com/2p98hsaf)

↑