Songwriting

by Bob Pegg

“Songs are unlike literature - they’re meant to be sung, not read.” Bob Dylan, in his Nobel Prize acceptance speech.

There’s a notion abroad that, in the timescale of human culture, song came first and poetry grew out of it. It’s an appealing idea, but who knows? Song and verse are certainly happy to help each other out. Burns and Scott re-jigged old songs for the page. Poets as diverse as Kipling, Auden, Charles Causley and Violet Jacob have used traditional ballad forms to frame original verses (and musicians have responded by putting tunes to their work). But Dylan’s point sticks. Shorn of its melody, the naked song lyric tends to shrivel on the page; but a seemingly banal set of words, when sung, can shake the heart. I’ve been writing songs for half a century and still find the form entrancing and mysterious, both to work in and to witness.

I came up through the British folk scene. My first visit to the Nottingham Folk Workshop was in 1960, when I was still at school. Skiffle and Rock and Roll (remember where you were when you first heard Heartbreak Hotel?) offered possibilities for the kind of music making that didn’t demand years of study and practice; and the informal, intimate atmosphere of the folk clubs was the perfect space for young performers to develop their talents. We bought cheap guitars, and taught ourselves the basic chords by trial and error and from instruction manuals - Bert Weedon’s Play in a Day is often spoken of with reverence by old folkies.

Songs with strong melodies and good stories made up the sturdy backbone of our repertoire. We already knew some English folk material from Singing Together sessions in primary school, when we gathered in the hall to bellow out old ballads like The Raggle Taggle Gypsies, and The Golden Vanity – bold tunes, and tales of adventure, bravery, passion, betrayal. Other material came from books, the radio, gramophone records; the Kingston Trio’s American murder ballad Tom Dooley was a great favourite, not least because you only needed two chords to accompany it.

The Tonight magazine programme, which went out on BBC TV early on weekday evenings, was a great source of material. It nearly always ended on a musical item; Robin Hall and Jimmy MacGregor maybe, with a Traveller song from North East Scotland, or Cy Grant singing a sweet Bahamian love lament. I would wait with the microphone from a little Grundig reel to reel tape machine held in front of the TV set's speaker, to record whatever was on offer. Then me and my mate Richard Jones would learn the songs from the tapes and perform them in the folk club the next Sunday evening.

Most folk clubs met once a week, usually in the smoky bar or function room of a pub. They nurtured artists as disparate as Billy Connolly, Barbara Dixon and Martin Carthy. During a typical evening you might hear blues, sea shanties, American Old Timey music, Durham miners’ songs, and a comic monologue or two. There was a solid core of original material as well, by writers like Matt McGinn and Ewan MacColl, and by the end of the sixties the idea of the singer songwriter was well established. Jake Thackray, influenced by the chansonnier Georges Brassens, was never off the TV. Sydney Carter had huge success with The Lord of the Dance. On the radio John Peel was championing Joni Mitchell and Bridget St John. Writing, performing and even recording your own material had become an exciting possibility.

In 1970, together with Carole Pegg, I put together the folk rock band Mr Fox, with an instrumental line-up inspired by the old Yorkshire Dales dance bands. We were heralded in The Guardian, shot at in Manchester; our first gig was the Royal Festival Hall, and our finest the Lakeland Lounge in Accrington. We had a contract with Transatlantic Records and we needed material, so I started to write.

The songs came easily. Subjects ranged through depopulation in the Yorkshire Dales, a hiker hanged by his rucksack, and the story of Mr Fox himself, a serial killer in an English folk tale which Shakespeare once heard. The years of singing in folk clubs (and of reading the Romantic poets) stood me in good stead, leaving the imprint of song forms that were easy to slip into: traditional ballads, waltzes, a proto-rap, with straightforward rhyme schemes and plain diction.

Now, it takes me much longer to write a song. I’ve learned that words or melody can arise together or independently, often just in fragments that may take years to flesh out, if they’re ever fleshed at all. A theme can sneak up and preoccupy you and you don’t know why. Then, when you have your story worked out (I’m keen on stories) and you begin to write, the song grabs the reins, gallops off, and you can land in quite a different destination from the one you had intended. That’s when you know that the Muse has smiled and the magic is working.

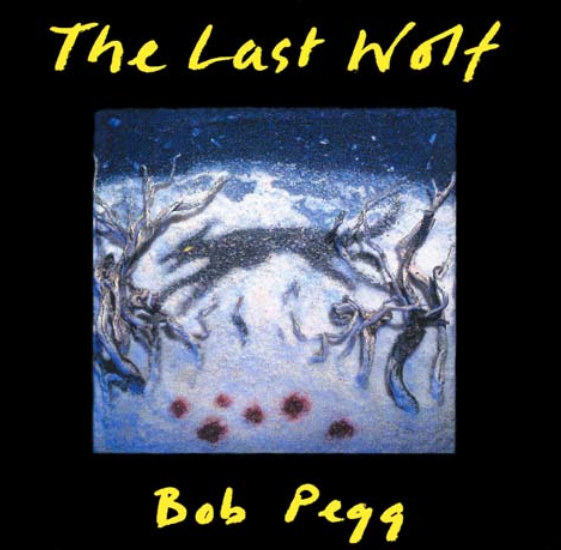

Kenny Taylor, Northwords Now editor, suggested I choose one of my songs and talk about how it was written, with an option for readers to download a recording. I’ve picked The Last Wolf, from the 1996 album of the same name.

A long-standing fascination with wolves took me to the places in the Highlands where the last survivors in Britain were slaughtered: Glen Loth, Cannich, the banks of the river Findhorn. Early on in the writing, images started to materialise: a pack of wolves running through shafts of sunlight in the primeval Caledonian forest; blood staining the snow on a winter hillside. Then came the phrase “I remember…” and with it the first suggestion that the voice of the song would be the voice of the last wolf itself, remembering for all wolves.

Quite quickly a melody began to coalesce around the words, circling an A minor chord on the guitar, with just a whiff of flamenco. With hindsight I think the shade of Lorca had slipped in, the lone wolf dying by the gun, body never found.

Words and melody emerged entwined, helped along by exploratory strumming. Verses started to come together, and each verse had four long lines, each with the same rhyme ending. Great columns of rhyming words began to stack up on the page, together with phrases and whole lines - crossed out, shuffled around, reinstated, crossed out again. In the end there were four verses. They follow a chronological sequence: the Edenic woodlands of Caledon; paradise lost to the arrow of a hunter; confusion, as a whole landscape is transformed; memories of the good times, and resignation to the inevitable.

Looking back on The Last Wolf, more than twenty years after it was recorded, it seems clear that it’s as much about human concerns - old age, security, nostalgia - as it is about wolves. That didn’t occur to me when I was writing it, but that’s not so surprising. One of my top songwriting tips, which I happily pass on to anyone thinking of writing their own song: just tell the story, and let the metaphors take care of themselves.

Mr Fox’s two albums, Mr Fox and The Gipsy, are both on the CD Mr Fox: Join Us In Our Game (Castle Music - CMRCD1049). The Last Wolf was reissued in 2018 (Talking Elephant - TECD401). You can hear both recordings on Spotify and purchase the CDs online.

| Bob Pegg: Songwriting | |

|---|---|

| Songwriting | Article by Bob Pegg |

| The Last Wolf | Audio by Bob Pegg |